“Theoria”

Charlie Rauh

Music has the power to console and enthrall. That’s been true for humans for an estimated 40,000 years. As blues star and former Baton Rouge resident Buddy Guy said of the musical genre he operates in: “The blues chase the blues away.” And New Orleans singer Aaron Neville often cites music’s healing power. “It’s like medicine to me,” he said.

Charlie Rauh's album, 'Theoria,' features Rauh’s solo guitar and three performances by the LSU A Capella Choir.

Countless YouTube videos of singing dogs and piano-playing cats suggest animals are not immune from music’s benevolent influence. Specific examples include British pianist Paul Barton playing Claude Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” for an 80-year-old elephant in Thailand. Another example, titled “AMAZING Animals Reacting to Music,” begins with a small girl playing a child-sized accordion for cows that run across a pasture and form a polite line as they listen to a jaunty little melody.

The latter video also includes a traditional jazz band entertaining its cow audience with “When the Saints Go Marching In”; birds reacting to wind instruments; elephants bouncing to boogie-woogie piano and swaying to a lively classical violin piece; and a young woman singing and playing ukulele for tigers.

In Baton Rouge last summer, guitarist and composer Charlie Rauh served as artist-in-residence at the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine. After observing veterinary clinicians and their animal patients, Rauh channeled his vet school residency into compositions for solo guitar and choir. Thirteen of the pieces appear on his album, “Theoria,” featuring Rauh’s solo guitar and three performances by the LSU A Capella Choir.

“I wanted to create a sound that could invite the sense of trust and hopefulness that defined my experience at the school, while not shying away from the emotional complexity inherent in medical treatment,” Rauh said.

Both the solo and vocal pieces are short, even fragmentary. The guitar music, especially, is intimate and dreamlike. Some relatively animated, jazz-like flourishes appear, but as Rauh plays with apropos gentleness throughout, reverie remains the dominate mood.

The album’s wordless vocal selections performed by the LSU A Capella Choir inevitably resemble ancient sacred chorale music — the Italian a cappella translates to church style. One vocal piece, the minor key “Theoria Part 12,” takes a darker turn, but the others are, like Rauh’s guitar selections, more examples of music’s beautifully consoling effect.

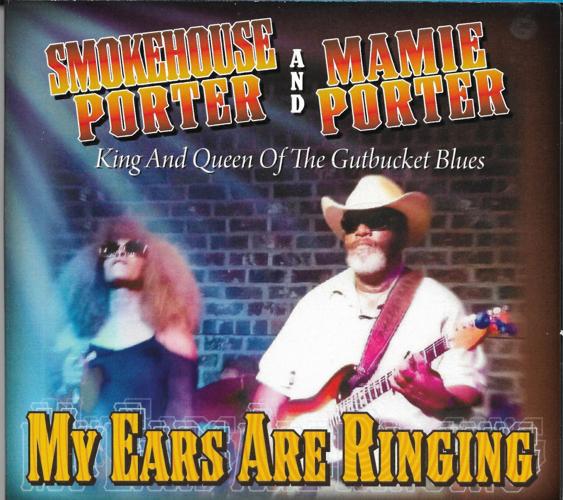

“My Ears Are Ringing”

Smokehouse Porter and Mamie Porter

Smokehouse Porter and Mamie Porter are married in the blues. No matter what song they’re singing, the Porters do it with down-home authenticity. After all, they’ve been singing the blues, together, for more than 30 years.

Smokehouse Porter describes his music as Louisiana swamp blues meets blues from the Mississippi Delta. That combination makes the couple’s “gutbucket” blues. The Porters’ latest album, “My Ears Are Ringing,” contains 10 original songs by Smokehouse Porter and Mamie Porter. They recorded the album with their Gutbucket Blues Band: Mark “Pineapple” Johnson, bass; Floyd Saizon, drums; Hogy Notzel, lead guitar; Gray Pettit, keyboards; and the late harmonica player Les “Boogie” Skinner, to whom the CD is dedicated.

The Mamie Porter-composed “Me and These Doggone Blues” moves to a lively tempo, good for dancing, even though the lyrics lament loneliness of the kind that the United States reportedly is so afflicted with these days. She sings of another kind of blues, also frequently experienced, in “The Flood of 2016.” The Porters were among the thousands in Louisiana whose homes were flooded that year.

Smokehouse Porter recounts a classic blues scenario in his composition, “She Dog.” Over a slow-churning tempo, he sings of a woman who doubts the veracity of her man’s absolute denial of having an affair. Mamie Porter sings backup vocals, emphasizing the lady’s cheating-man dilemma.

Authentic blues people, the Porters express their feelings, thoughts and experiences in song. Backed by a lubricious blues groove, Mamie Porter, for instance, defends and explains her music in two selections, “Leave My Blues Alone” and “I Didn’t Choose the Blues.” Smokehouse Porter, soulfully backed by his wife, counters his own naysayers with “My Ears Are Ringing.” “People say I can’t sing these blues,” he said. “They say I can’t even play my guitar. I don’t give a damn about what people say, I’m go’ play these my own damn way.”