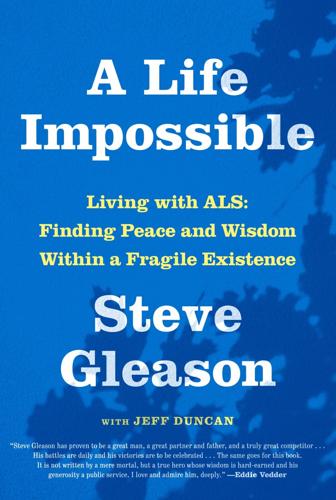

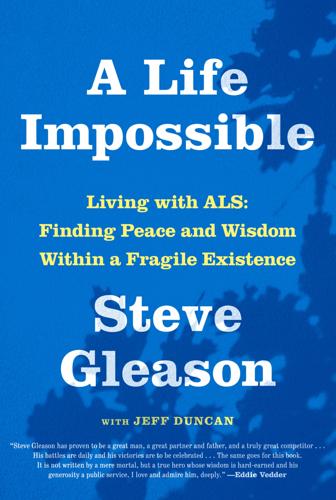

(The following is an excerpt from former New Orleans Saints standout Steve Gleason’s new book “A Life Impossible,” released April 30 by Alfred A. Knopf Publishing.)

In 2004, on the Thursday afternoon of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in the main food vendor area, somewhere near the cochon de lait stand, amongst the joyfully sweaty music lovers and Native American war drums thrumming nearby, my world collided with the world of Michel Varisco.

That encounter changed the course of both of our lives.

Michel went to the University of Colorado with Bart Morse. Bart and I knew each other through some of my good friends from Gonzaga Prep, who were in the same fraternity at the University of Washington as some of Bart’s buddies.

In 2004, Bart called me and said he was thinking about coming to New Orleans for Jazz Fest, which I thought was a stellar idea.

For a music lover like me, Jazz Fest is one of the highlights of the year. I’ve been a regular since 2001, when I attended the Fest by myself during spring workouts before my second season with the New Orleans Saints. I was so impressed by the community and culture, I vowed to attend every year if I was fortunate enough to make the team.

On the call, Bart mentioned that his friend from college, Michel Varisco, lived in New Orleans; he thought we should try to hang out with her at some point.

Bart’s exact words were “Michel is a really cool chick, Steve-O.”

I had moved into an apartment in Uptown New Orleans. Most of my teammates either lived in the gated communities of the surrounding suburbs or in high-end condos downtown, but I wanted to get a taste of the real culture and texture of the city. I was one of the few players, if not the only player, living in Uptown at the time.

The apartment was located in a large, old, oddly designed house owned by the Patterson family and located on the northeast corner of Coliseum Street and Louisiana Avenue.

I lived in one of the first-floor rooms in the back portion of the complex, which made it feel like a quaint boutique motel. My apartment was maybe 500 square feet, with high ceilings and lots of windows. Outside the front door there was a small pool. Above the pool, the owner had built a giant trellis, which held grapevines for his homemade wine.

Writing about it now conjures beautiful images and strong feelings of nostalgia. This is the place where I grew to love New Orleans, and one of its daughters.

Bart flew into New Orleans a day or two before the Thursday of Jazz Fest and stayed at my place. My brother, Kyle, was also staying with me, as he often did. The three of us spent our days hanging out, playing guitar, barbecuing, swimming, and talking about our various life philosophies.

On the Wednesday before Jazz Fest’s second weekend, Bart called Michel to see what she was up to. She told him that the next day — “Locals’ Thursday,” as New Orleanians called it — was a special one because of the annual Jazz Fest Triathlon, known as the JFT.

Bart, Kyle, and I were curious: “A triathlon during Jazz Fest?!” We all assumed it was a serious, competitive event.

Michel explained that the JFT is essentially drunken revelry, structured around an informal, made-up “triathlon.” A bunch of her brothers’ friends from Jesuit High School in New Orleans had started the tradition. The group would gather at the New Orleans Museum of Art in City Park and bike 1.5 miles to the festival, which is held in the infield at the Fair Grounds Race Course. Around 5 p.m. that afternoon, they’d compete in the second leg of the JFT, a run around the Fair Grounds’ one-mile dirt racetrack. Finally, there would be a swim in Bayou St. John, where according to Michel, guys would wear women’s swimsuits and other homemade costumes. Each leg of the triathlon would feature a “shotgun start,” where every participant was required to “shotgun” a beer before going past the starting line.

Bart got off the phone and explained everything to me and Kyle. We all agreed that it sounded awesome. Stoked, we headed off to Walgreens to buy swim caps for the bayou swim.

I don’t remember having any expectations about Michel before meeting her. If anything, my expectations were low. The women I’d met in New Orleans were, how should I put it, ordinary, compared to my past. Fairly superficial, materialistic, and not interested in any type of exploration. During my first four years in New Orleans, I hadn’t had any significant relationships.

Girls weren’t really a top priority for me early in my career. I was focused on playing football and exploring the world.

So I had no expectations when Bart, Kyle, and I showed up at Locals’ Thursday. It was a typically humid New Orleans spring day, with the sun peeking through the clouds, baking the tens of thousands of locals in the crowd. Four years into my New Orleans tenure, I felt I could lay claim to being one of them. I mean, I was standing there eating boudin balls in a swim cap — that’s as New Orleans as it gets, right? Then out of nowhere Michel appeared, a small, tan girl, with her thick mane of brown hair up in two buns on each side of her head. She was wearing a weathered red shirt proclaiming “Everyone Loves an Italian Girl.” She kissed Bart on the cheek, walked over, and stood in front of me quite boldly. She looked down at my flip-flops, then looked at my shirt, then her huge brown eyes stared fiercely into my eyes.

She paused, a slightly puzzled look on her face. Four heartbeats later, she quipped, “Steve, you’re a lot cuter than you look.”

Intrigued at first sight

Half of me was confused with that intro, and the other half was pleasantly amused. I responded, “Uh ... Hi, I’m Steve.” And I thought, hmm, maybe this cute, bold Italian was not an ordinary girl after all. Michel’s disarming, Yogi Berra logic put a smile on my face. She smiled, too, and came in with a kiss on the cheek.

I wouldn’t call this a love-at-first-sight moment. I’m not a love at-first-sight guy. I don’t think that even exists.

But I was intrigued.

Kyle went off to the ATM while we munched on some Jazz Fest grub. Michel excitedly told us it was time for the watermelon sacrifice. Watermelon sacrifice?! She failed to mention that on the phone the night before.

As Michel, Bart, Kyle, and I arrived at the Fais Do Do stage, some obscure afternoon musical act was wrapping up its set. The JFT participants were a mash-up of ragamuffin artists, bankers, bartenders, and slightly less ragamuffin stock traders, lawyers, Marines, teachers, and since my initial 2004 participation, NFL football players. Like a rising tide, this beautiful flock of JFT urchins gravitated together, orbiting around an older, sun-drenched man who was dressed in a jumbled mishmash of legitimate running gear, equally legitimate voodoo garb, and a not-quite-legitimate ballerina tutu — this was the Watermelon Man.

Carrying on a family tradition, Rivers Gleason, son of Steve and Michel Gleason, totes the watermelon during the annual Jazz Fest watermelon sacrifice on April 26.

Out of nowhere, a watermelon appeared in the trampled, muddy grass. Immediately people started piously chanting some droning mantra and satirically dancing, while swirling around the sacred fruit, like planets orbiting a star.

Watermelon, watermelon, red to the rind,

If you don’t believe me, pull down your blind.

As I danced and sang with the hodgepodge congregation, I realized this was less satire than a truly reverential celebration of life in New Orleans — with all its sultry imperfections and sideways beauty.

Sell it to the rich, sell it to the poor ...

Sell it to the woman standing in that doooOOOOooor.

After an uncomfortably, mesmerizingly long time, the Watermelon Man threw the melon high in the sky.

Pure, unbridled joy

The watermelon crashed to the earth, exploded, and everyone pounced. Rabidly, they snagged pieces of the sacrifice off the sloppy turf and shoved them into their mouths, their faces dripping with red juice.

I joined right in. Basking in pure, unbridled joy.

The next JFT event was the mile (8 furlongs) run around the Fair Grounds horse track. Then it was on to the final leg of the triathlon.

While the watermelon sacrifice was transformative, the finale sealed the JFT inauguration for me.

When Jazz Fest concluded at dusk, we left the Fair Grounds and walked to Our Lady of the Rosary Catholic Church, a small, ancient domed church adjacent to Cabrini High School, the all-girls Catholic school founded in 1905. The JFT group gathered in the parking lot of the Cabrini campus, which sits just across Moss Street from Bayou St. John.

The “triathletes” were dressed in various costumes, ranging from full-bodied, papier-mâché sharks to women’s swimsuits worn by grown men. Some guys had water wings. I felt right at home, though slightly under-costumed in my swim cap. I was in my element, Peter Pan in Neverland.

I had never swum in Bayou St. John, nor in any of the warm, murky waters of the South. I took off my shoes, and we all found the imaginary starting line for the shotgun start. Beers downed, our disheveled crew of costumed warriors stampeded through the Cabrini parking lot toward the bayou, took a right turn on to Moss Street, then found our way to the banks of the bayou just past the Magnolia Bridge. Several people started diving into the murky brown water.

We swam through the chocolate, papier-mâché-melting waters, right next to the chrome-silver Magnolia Bridge. Then we migrated back to the Cabrini parking lot, where JFT co-founder Hunter Higgins christened the day by bestowing spoof awards on a few people. We all collapsed in a pile of joyful exhaustion.

We ended up hanging out with this group later that night at a place in the Marigny neighborhood, just east of the French Quarter. Bart, Kyle, Michel, and I gathered around a wobbly wood café table with a few others until the wee hours of the morning.

A few days later, Michel came over to my apartment to hang with me, Kyle, and Brendan. I loved her transparency and realness. Michel had and still has this unique ability to say things that are borderline offensive, but people love her more for it. Like her remark to me the first time we met: “You’re a lot cuter than you look!” It was like a Zen koan.

I’d grown to appreciate the unique underbelly of New Orleans, but this was the first time I’d been so close to it and experienced it through a group of such remarkable people. In Michel, her family, and her friends, I had found kindred spirits, people who shared my love of life.

'That girl is awesome'

Kyle and Brendan lived with me on and off during the 2004 season and we’d grown exceptionally close. We were a tough threesome to break into. But Michel had come over frequently throughout that year, and almost immediately we became a foursome. Kyle, Brendan, and I really had a love for Michel and her bright, honest spirit. She wore blue jeans, trucker hats, T-shirts, and Converse All-Stars. She was so much like us. She was really cute and one of the boys, too, this tiny, sprite-like bundle of energy, who would sit outside on the little concrete stoop that led to the courtyard at my apartment and captivate our group with stories.

One night, the three of us were sitting on the floor, under the bedroom loft. Michel had just left, and I told Kyle and Brendan, “Damn, that girl is awesome. If one of us doesn’t marry her, we’re a bunch of dummies.”

I’m no dummy.

Over the next few months, we hung out every day, as best friends. We went to the movies, read books aloud to each other, heard live music with her brothers, had dinner with her parents, and took her grandfather to lunch.

A few nights after the season ended, we were out at Cosimo’s, a historic dive bar on Burgundy Street in the French Quarter. We sat at a small square table, zoned in only to each other. After a couple of martinis, with some nervous energy Michel said, “Steve, I had a dream that you were dating my friend Ainslie but that we snuck on the other side of the levee and I kissed you anyway.” After a moment’s pause she said, “Usually it takes a day to stop feeling the feelings of my dreams, but this one won’t go away even though I’ve tried to make it go away.” And then, with her eyes looking at her feet, she said, “I think I like you.”

I think I also knew at the time that we liked each other, but I was hesitant to go there. At least not just yet. We got to my house that night at 4:30 a.m. so I asked her to stay over. She did, but I didn’t make a move.

A couple nights later I went out to dinner with Michel and her brother Pauly at Rock-n-Sake, a sushi restaurant in the Warehouse District of New Orleans. Our conversation turned to adventure. I told them about the upcoming trip to New Zealand I had planned during the offseason.

“Man,” Michel said, restlessly. “I need some adventure in my life.”

“Well, this isn’t super-adventurous, but I’m driving across the country in a couple days,” I said.

I paused for a moment, as we all looked at one another, then I added, “You should come!”

She waffled. She mumbled something about having to work and that she would need to get her parents’ approval. Yes, at twenty-seven, Michel, being the good Italian girl that she was, needed to run the idea past her mom. But Pauly endorsed the idea.

It was not easy to get a yes from Michel, but after getting her whole family’s approval, she decided to come with me on the four-day journey from New Orleans to Spokane. We took my bio-diesel pickup truck, which Michel thought smelled like Popeyes chicken because it ran on vegetable oil instead of gasoline.

Relationships and rebellion

Midway through Texas we began talking about our past relationships and rebellious days. I’d already heard about some of her ex-relationships and wild past, but we hadn’t talked much about mine. I told her about the one girl I’d dated for three years in high school, Jen Austin.

She asked me how many people I’d slept with, and I told her none. After I dated Jen, I told myself that I wasn’t going to have sex with someone until I have a similar connection, a true friendship with a girl. She was as surprised as I’m sure everyone reading this book is. She’d playfully brought with her a shiny red copy of the Kama Sutra, and very carefully put it back in her bag.

On the second night, we stopped at a hot spring in Winter Park, Colorado. We were alone, under the stars, looking at the perfectly lit snow-capped mountains. It was that scene where the new couple kisses for the first time. This was the moment. I was hesitant. Michel clearly noticed, confused.

“You’re such a good friend of mine,” I told her. “I don’t want to mess this up.”

I knew this was going to go one of two ways. Either we were going to date for a while, and then we’d eventually break up, which would be one of the worst things I could imagine. Or ... we were going to get married and be together forever. Period. Those were the only two options. Was I ready for this? Both options were scary.

The next night, after a long day of driving, a guy with bare feet and a shirt that said “Holy S---” checked us into a hostel. We lay there and hugged and Michel asked, “So ... We still can’t kiss?” This time, I relented. But before we kissed, I laid down a ground rule: “We have such a good friendship, if this is awkward for you or for me, I think we should stop and make it so we can still be friends.”

She took the “awkward” line to mean that she needed to be a really good kisser. And she was. It wasn’t awkward. It was best friends ascending to love. It was beautiful. And perfect. We fit well together and it was not weird at all.

Our relationship gradually developed into something that I think only a few people ever discover. Soul meets body stuff.

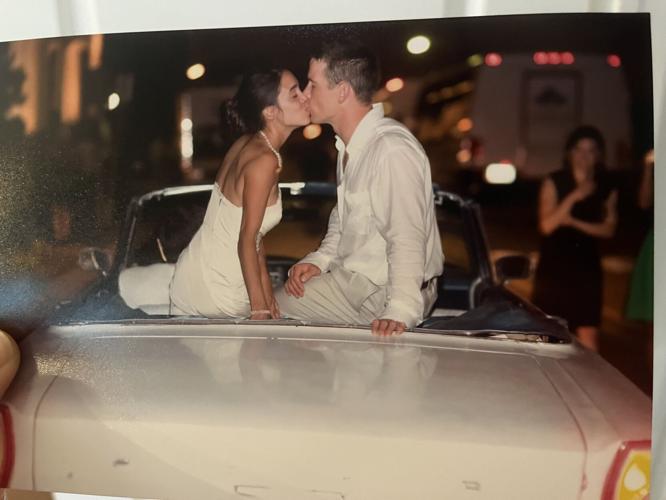

Michel Varisco and Steve Gleason were married in New Orleans on May 16, 2008.

BOOK EVENTS

Co-authors Steve Gleason and Jeff Duncan will appear at two upcoming events to present "A Life Impossible."

WHERE: Octavia Books, 513 Octavia St., New Orleans

WHEN: 6 p.m. May 9

*************

WHERE: Garden District Book Shop

The Rink, 2727 Prytania St., New Orleans

WHEN: 11 a.m. May 11