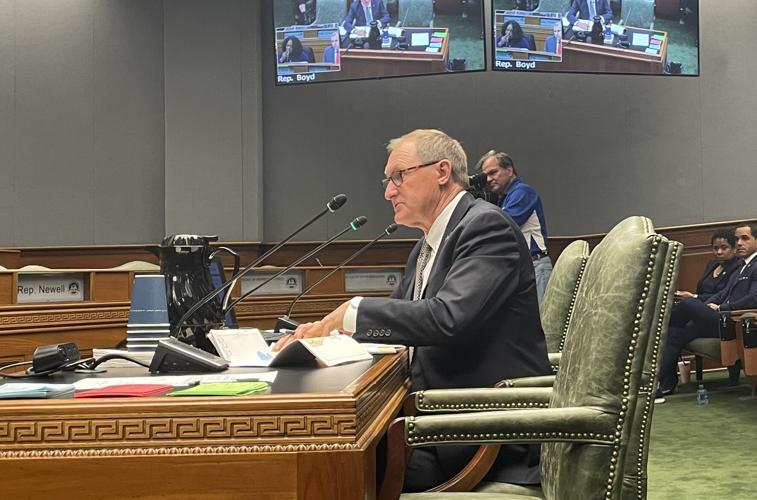

WASHINGTON — Just after taking office in January, Gov. Jeff Landry called a special session to replace the congressional maps approved by the Legislature in 2022 with ones that would create a second Black majority district likely to elect a Democrat this fall.

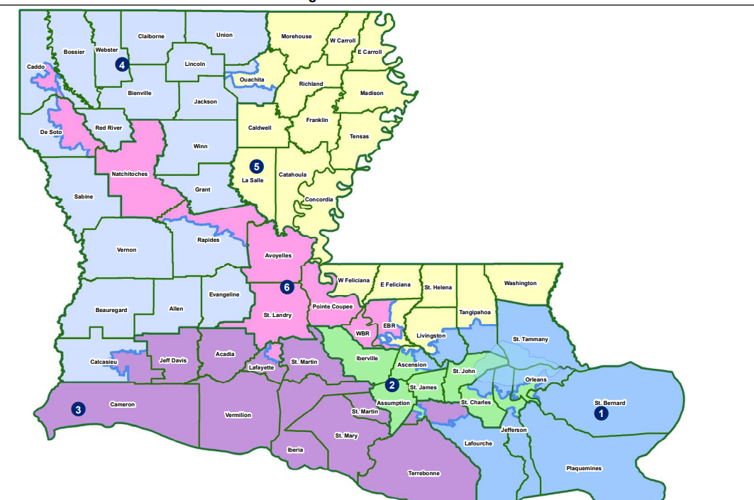

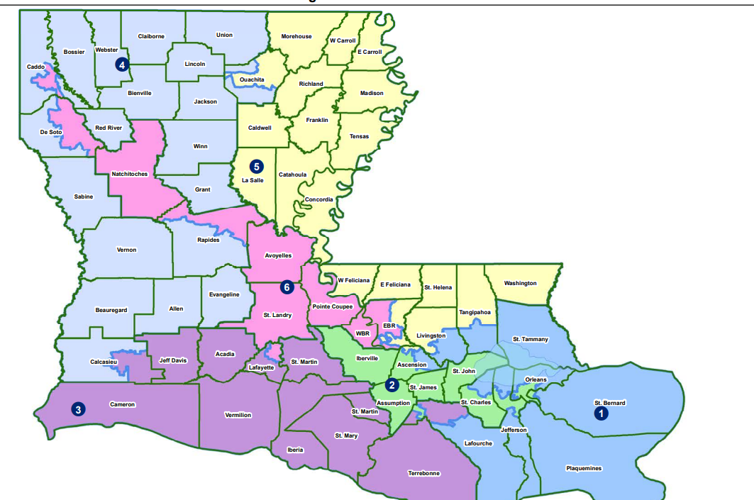

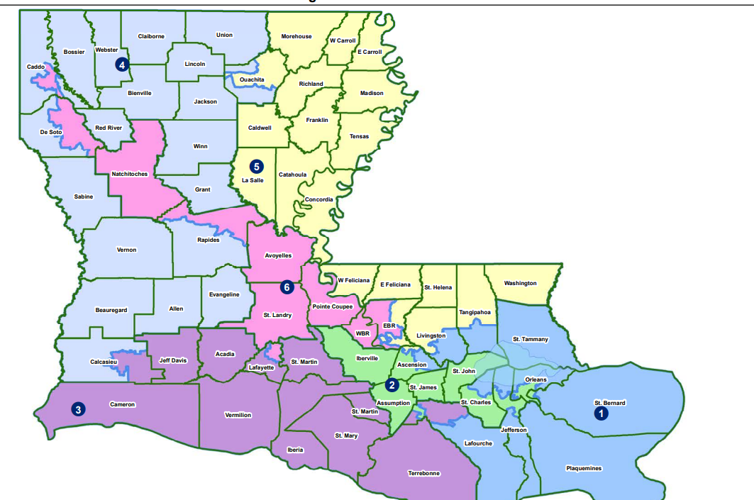

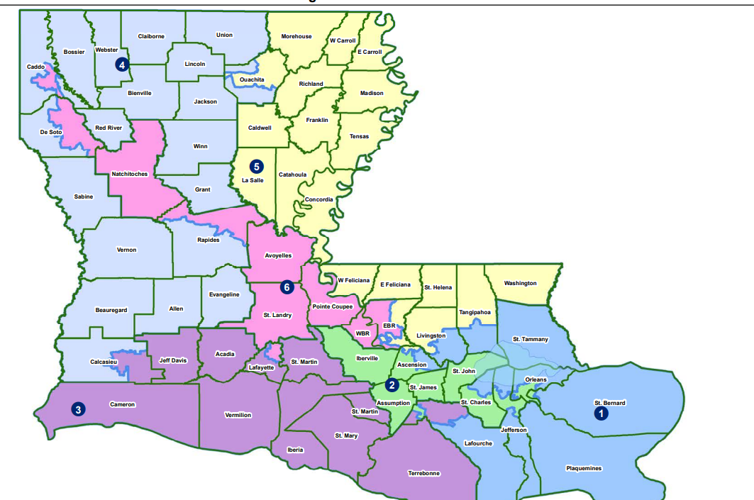

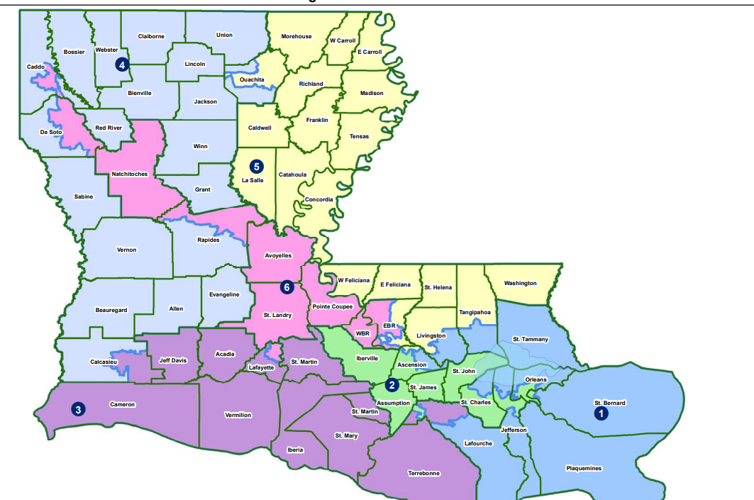

Federal courts had judged the 2022 maps wanting because they grouped voters in a way meant to keep the Louisiana's congressional delegation’s lineup the same, with five White Republicans and one Black Democrat. On Jan. 22, Landry, a Republican, signed into law new election maps that dramatically redrew the 6th Congressional District, which had been based around the capital region and is currently represented by U.S. Rep. Garret Graves, a White Republican from Baton Rouge. The new map created a second Black majority district that now looks like a lap-and-shoulder seat belt stretching across the state to include parts of Baton Rouge, Acadiana, Alexandria and Shreveport.

Even with two attempts in as many years to redraw the maps, the issue remains unsettled. The incumbents — and their challengers — are antsy over which voters they'll have to appeal to as campaigns gear up over the summer. Perhaps no one has a bigger interest in the case than Graves.

The issue will be decided by a special panel of three judges appointed by the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. A trial is set for April 8-9 in Shreveport to consider if the Legislature’s latest map is constitutional.

The judges essentially have three options: Keep the Legislature’s latest map, order lawmakers back to the drawing board or draw their own maps.

On the panel are 5th Circuit Judge Carl E. Stewart, who was nominated by President Bill Clinton and sits in Shreveport, and U.S. District Judges Judge Robert R. Summerhays and David C. Joseph, both nominated by President Donald Trump and sitting in Lafayette. The panel already has set a May deadline for a decision so candidates can know the districts they’ll run in for the Nov. 5 election.

While of particular interest to Louisiana, the outcome of the Callais vs. Landry case also has gotten national attention. The announcement that Colorado conservative Rep. Ken Buck would resign next week leaves House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-Benton, with a bare Republican majority.

The new maps approved by the Legislature and Landry raised the percentage of Black voters in the 6th Congressional District from 25% to 56%. Legislators said they created the second minority-majority district on the orders of federal judges, adding that defending the old districts would cost tens of millions of dollars in legal fees.

Chief U.S. District Judge Shelly Dick of Baton Rouge, nominated by President Barack Obama, said in a 2022 opinion that two minority-majority districts are necessary under the Voting Rights Act. The case was paused before a trial could be held and a definitive order issued. The U.S. Supreme Court in the meantime considered a similar Alabama case and found the need for a second minority-majority district in that state.

Many posited that the Legislature’s latest maps were an expression of Landry’s efforts to punish Graves for not supporting him in last fall’s gubernatorial campaign, thus diminishing the political fortunes of a likely future rival. Graves won’t comment on those claims, which tend to be whispered but not articulated publicly among Louisiana’s political class.

But from the moment the new maps were approved Jan. 19 by the Legislature, Graves has vowed to run again for Congress. Graves said Wednesday he is confident the three-judge panel will throw out the Legislature’s January map and order new ones that return the Baton Rouge area to being represented by two congress members instead of the four contemplated by the current maps.

He notes the Legislature’s January maps were composed quickly and passed in four days. The public was not allowed input and the maps were drawn primarily to group Black voters into a majority, which violates provisions of the Voting Rights Act, he argues. Federal law requires that, in addition to not breaking apart minority communities, districts must be compact and include voters with similar interests.

“If you have a district that goes from Ascension Parish to Livingston Parish to LSU’s campus to Monroe, which committee do you want to get on?” Graves asked. “Do you want to get on Transportation Committee? Do you want to get on the Ag Committee? You’ve lost the focus.”

Population breakdowns of new congressional districts

To make the numbers work, the Legislature moved precincts in the other five districts, particularly in the 2nd Congressional District, lowering the percentage of Black voters there from 61% to 53%. It is the state’s only minority-majority district, stretching up the Mississippi River from New Orleans East to north Baton Rouge,

But Rep. Troy Carter, D-New Orleans, who represents the 2nd District, said creating a second Black majority district has been the goal of the minority community since the 2020 Census found that roughly a third of the state’s population is African American.

“Three divided by six is two,” Carter said, repeating what became a mantra by Louisiana’s minorities demanding to be better represented in Congress.

Carter said Wednesday that he understood he "was going to take a bit of a haircut" in terms of Black voters and that drawing a second minority-majority district would entail trimming the 2nd District.

“I don’t want to see anything that could dilute the chance of second minority-majority district,” he added.

G. Pearson Cross, a professor at University of Louisiana-Monroe, noted this is not the first time federal courts have weighed in on Louisiana’s efforts to gerrymander Black-majority districts.

In the 1990s, a three-judge federal panel threw out the so-called “Mark of Zorro” district that zigzagged from Baton Rouge to Shreveport, picking up Black precincts along the way. The Legislature came back with a "seat belt" configuration, similar to one approved in January, that began in Baton Rouge and went to Shreveport. That map also was rejected by the federal courts.

“The courts have been pretty consistent in saying that redrawing based solely on race is unconstitutional,” Cross said.

In many ways. three of the maps presented and rejected by the Republican-majority Legislature in 2022 would have been easier to defend, Cross said. The configurations would have recast the Monroe-based 5th Congressional District to move up the Mississippi River from the predominantly Black neighborhoods of north Baton Rouge.

“That would have been more compact, contained communities of interest and required fewer changes to the 2nd Congressional District,” Cross said.